Writer of the Month: Muli Amaye

Tell me something interesting about yourself. What got you into writing?

I have always made up stories. Even when I worked in offices and had to write official letters. I remember I temped at a place called ‘Our Dogs’ which was a newspaper all about dogs (go figure) and the boss asked me to respond to a complaint. I wrote a two-page missive about someone going AWOL and used so many metaphors and fictionalised scenarios that even while my boss was laughing he was showing me the door. I started writing seriously when I started my undergraduate degree at MMU and took a creative writing module. I found that all the stories I would tell my son at bedtime fed beautifully into stories on the page.

Your debut novel, A House with No Angels is out this month. What were your inspirations for telling this particular story?

I didn’t know this was the story I was going to tell. I first met my father in 1996 in Nigeria. He told me about arriving in Cardiff in 1950 and then moving to Manchester to complete his Masters in Civil Engineering. He said the communists sent him. That alone sparked my interest. I began my research looking for links between communism and Nigeria and Manchester and the story grew from there. I found information in the Labour Archives about the Pan African Congress in 1945 that took place in Manchester and all the photographs I looked at had African/Caribbean men and white British women. It made me curious as to why there were no African women in the pictures. I decided to insert them into the congress and into life in Manchester from the 1940s.

Your novel explores several important and powerful themes including Pan Africanism, mental health and Black womanhood. What approach did you take to making these themes accessible for a wide readership?

I wanted to tell a human story. I wanted to give people a glimpse into ordinary lives of women who work, struggle, politicise, mother, love and lose. I decided that telling individual stories of connected women would provide a platform for intergenerational exploration, the effects of politics on women particularly black or mixed women, and the way second and third generation negotiate the space that they occupy in Britain, personally and politically. By telling the stories of their hopes and desires and presenting their flaws, I hope that the little stories are ways of giving the bigger picture to a wider audience.

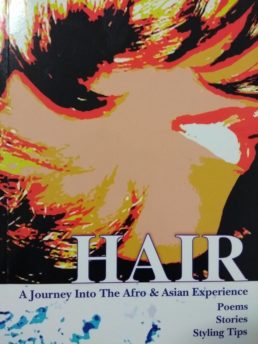

Your novel takes an original and refreshing approach to including a mixed race protagonist without playing on stereotypes of mixed race experiences. What do you hope this communicates to readers? What changes do you think the literature industry needs to undergo to dismantle limited representations of people of colour?

Being of mixed race and raised with the influence of one of those cultural spaces and not having access to the other, is an all too familiar happening. In AHWNA, I make reference to babies born during the second world war who were put into care, hidden away – think Delaney’s A Taste of Honey – and the problems attached to having a child of mixed heritage. My studies referenced the Tragic Mulatto, the mixed-race person who is sad or suicidal because they do not fit into either black or white society. I decided that Elizabeth, my mixed-race protagonist, was not going to entertain that trope, but would in fact define herself and her own personal issues.

It is about time that the industry took a large step back from ‘racesplaining’ how people of colour should be presented in literature. It is 2019 and we are no longer an anomaly on the page, we have shown that we are people, too. Imagine that! We are capable of defining our own lives in our own ways that do not have to include drugs, guns, gangs and killings. We no longer have to sit in the margins as though we are a bookend holding up the main story. We are our stories. We have the ability to tell a tale that is universal and that everyone can read and enjoy no matter their race, gender or any space they occupy in this world. The literature industry needs to stop trying to colonise our stories under the disguise of being inclusive and acknowledge that we have the right to tell our truths in our own ways.

You’ve completed a PhD in Creative Writing and you’re now working at the University of the West Indies. What advice and tips would you give to aspiring PhD candidates?

My PhD at Lancaster University did a number of things for me and my writing. It gave me space to explore both critically and analytically the subject I wanted to write about. I was asked recently, ‘What actually is a PhD in Creative Writing?’, by someone with a PhD in literature. I don’t want to point out the obvious here, but literature is creative writing… Every novel that is read and analysed is creative writing. I also pointed to the contents page of my bound PhD copy that I keep in my office and showed the one line that is my novel and the five chapters and all the subchapters that are my thesis! I am glad I did a PhD, not only for my own writing, but because I gained the skills needed in order to teach at a tertiary level and give the best advice to my students. Doing a Masters or a PhD in creative writing pushes you to fully consider where your writing sits in the canon and consider the boundaries you are pushing and why. Even for people who wish to write popular fiction as oppose to literary fiction, a degree in creative writing is a great route for ensuring your writing stands out from the crowd and gives you a full understanding of what it is you are doing and why.

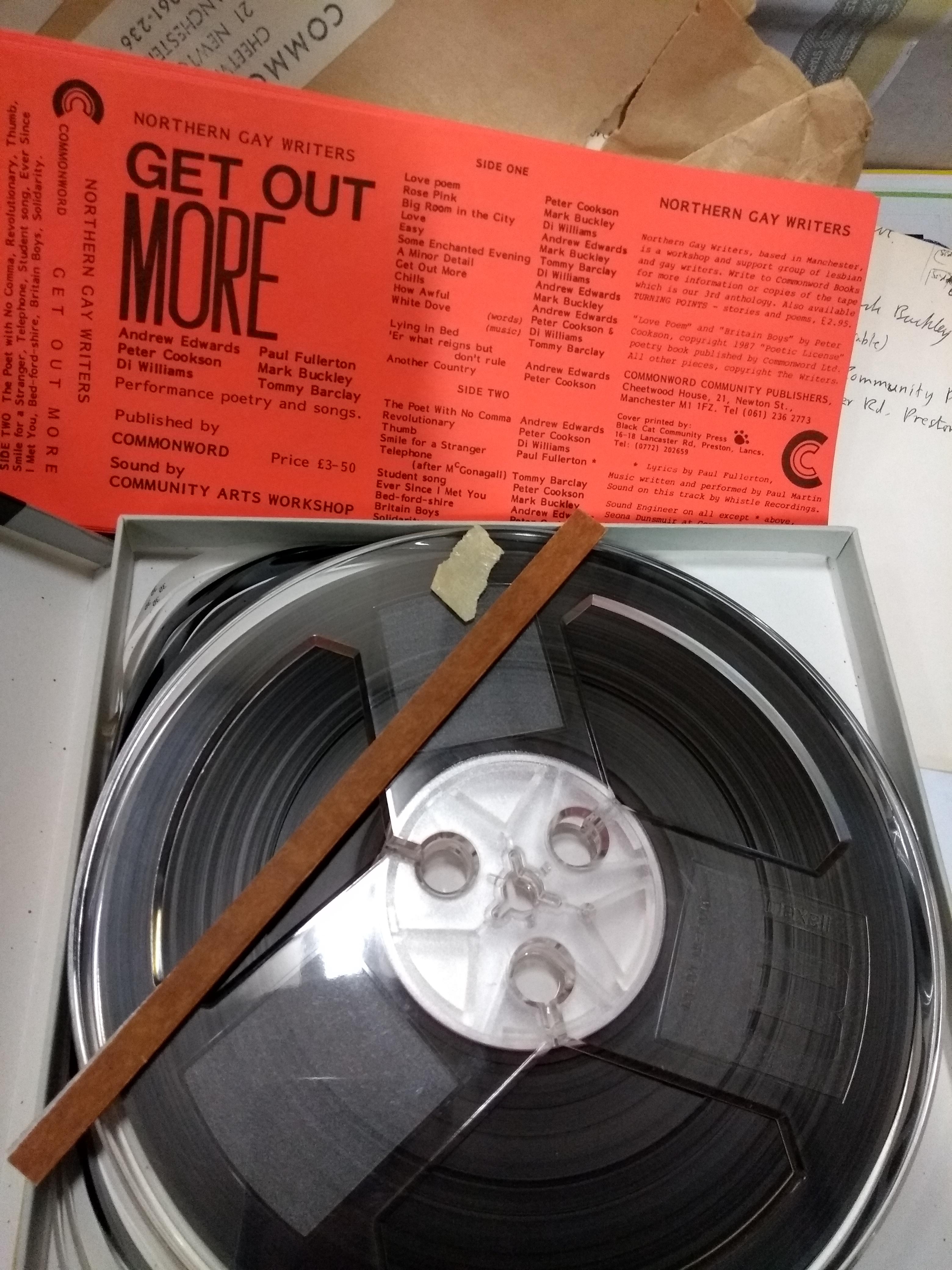

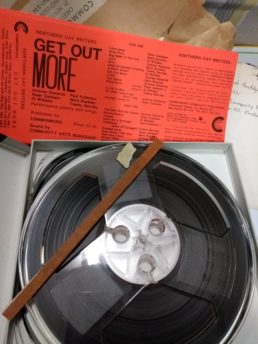

You have been a writer at Commonword for many years and attended our Advanced Black Novelists group. What is your best memory from this time and what did you learn about yourself as a writer during those years?

I think one of my best memories from the Advanced Black Novelists group was my first visit. I didn’t know what to expect and as I sat in the basement confident with what I had presented because I’d been through a Masters in creative writing, my writing was brutally pulled to pieces. It was a very important learning experience that showed me the difference between a seminar room full of polite students and a room full of writers who demanded more. It also gave me a place to develop my ‘black’ writing without having to explain certain aspects of it to people without the black experience. It was a great place to explore and discover who I am as a writer. Over the years watching other people’s writing grow from the feedback they received and the support and encouragement we gave to each other was wonderful.

What advice would you give to aspiring novelists when it comes to approaching publishers and venues with their work?

Believe in what you have written. Also listen to the feedback you are given as you approach publishers and consider what that means, i.e. whether you will have to compromise yourself and your writing to make a fit. Choose carefully. See what else has been published by them and decide if your work is in line with their ethos.

What does the future hold for you in your writing career?

I am writing. Constantly. I have another novel that was longlisted for the SI Leeds Literary Prize in 2014 and I’m about ready to go back to that and edit. I have a collection of short stories that I’m still working on and ideas for at least two more novels are lurking. I’m also writing a lot of poetry at the moment so who knows, that could also see the light of day some time soon. I will carry on teaching on the MFA in The UWI in Trinidad, it’s something I love and I find my students teach me as I teach them.

Where can we find out more about you and your work?

I have a website, that I’m trying really hard to keep up to date www.muliamaye.com. I have short stories published in various journals and magazines, but don’t look for them, they’ll be going in my collection! I’m on twitter @muliamaye (I’m worse at that than my website, but I’ll try harder)

Sum up your experience thus far in one word

Humbling